A long time ago, when I was a young and keen cub reporter, I was asked to take part in a live broadcast on the national BBC TV news.

This anecdote is of such vintage that I can’t even recall what the story was that I was supposed to speak about, though it was clearly something which had made headlines beyond our shores.

The bulletin was anchored from London and, in a time before laptops with cameras, I was asked to go to Broadcasting House in Belfast.

When I got there, I was taken to a room where a camera was pointed directly at my face and an earpiece fitted. Checks were carried out and then a countdown began until the moment when I would go live.

I started to become nervous. All of the facts and opinions I had rehearsed, popped and disappeared like bubbles in the breeze. The impersonal setting made it worse. I could hear the London studio, but I could not see it and was instead staring straight into a dark camera lens.

And then, with seconds to go before I was due to go live, my earpiece fell out. I froze and was in danger of being completely overwhelmed by panic. A calm producer came to my assistance, replaced the earpiece and moved away just before I heard a voice say, ‘And now we’re joined from Belfast by Jonny McCambridge….’

Everything after that is a blur. I am sure the clip exists in a big BBC vault somewhere, but I’ve never seen it and I’m fairly certain I don’t want to. I am merely thankful that it didn’t end up as an outtake on ‘It’ll be Alright on the Night’.

Since then I have become more used to doing broadcast. I’ve been on the radio often and made the occasional TV appearance. However, I can’t remember ever doing live TV again.

Part of this is because I have not been asked. I can’t prove it, but I suspect there is picture of my startled, blushing face from that bulletin years ago posted onto walls in BBC TV studios everywhere with the instruction ‘DO NOT BOOK THIS MAN!’

In addition, there are countless journalists, much more opinionated than I, who are available and can do a better job. My own particular shtick of the culchie who doesn’t really know what he thinks and just wants everybody to like him is never likely to translate into current affairs TV gold.

However, even if I was asked to go live again, I’m not sure I would be keen. I remember too well the terror. Giving good analysis on the news requires a calm, relaxed mind, not a sense of wild disorder like a zoo where all the animals have escaped.

Peculiarly, this phobia does not extend to radio. I’ve done live radio broadcasts in the studio, at home or on location and always been fine. On one occasion, after a mix-up over times, I was called and put on the air while the listeners were blissfully unaware that I was in the bath.

The recent news agenda has been punishing. I have worked long hours and a hotel room in Ballymena became my temporary home. It is one of the rare occasions when news organisations internationally have shown an interest in Northern Ireland.

After a late night and less than two hours of sleep, I am up early to fulfil a couple of radio commitments. As I am recording a piece for a Scottish channel, my employer sends on another request from an Australian broadcaster. Add it to the list.

I make contact and a link is sent to my email. This is unusual, but not unknown; some radio programmes prefer to connect with conferencing platforms which give better and more reliable audio than mobile phones.

I bounce from one interview to the next. I click on the link and an Australian man greets me and says audio is good.

Then, confusingly, he asks me to shift my laptop back a little and move the cover slightly forward. I comply without thinking. He then tells me he will put me through.

A newsroom appears on my laptop screen complete with a scrolling news ticker and an immaculately presented and coiffured presenter. She is talking about the situation in Gaza. The scale of my error becomes clear; in 30 seconds I will be on live TV across Australia.

I quickly glance at the mirror. My face is flabby and tired, my hair a bird’s nest, my beard a wiry mess. I am wearing the old, torn and stained grey T-shirt which I slept in. I look like a man who has been covering riots for several days with virtually no rest. I notice behind me that the door to the bathroom in my hotel room is open and the toilet is partially visible.

‘And now we’re joined from Ballymena by Jonny McCambridge….’

The interview passes slowly. Each time I think it has reached an obvious conclusion the presenter thinks of a new question to continue the ordeal. I see my own worn and tortured features staring back at me and have to stop from flinching.

Then it is over. I did not suffer the stage-fright which overcame me the last time I did live TV. I know that my answers were competent and professional. But it is the state of my appearance which is the concern. I looked like Worzel Gummidge with a hangover, on a really bad day.

I call my wife, who works in TV, and knows the importance of image on that medium. She consoles me by laughing uproariously.

My concerns over creating a bad impression are balanced by the fact that this was broadcast on the other side of the world. At least nobody I know is ever likely to see it.

My phone buzzes. There is a message from my Da.

It reads: ‘My friend saw you on the telly in Australia….’

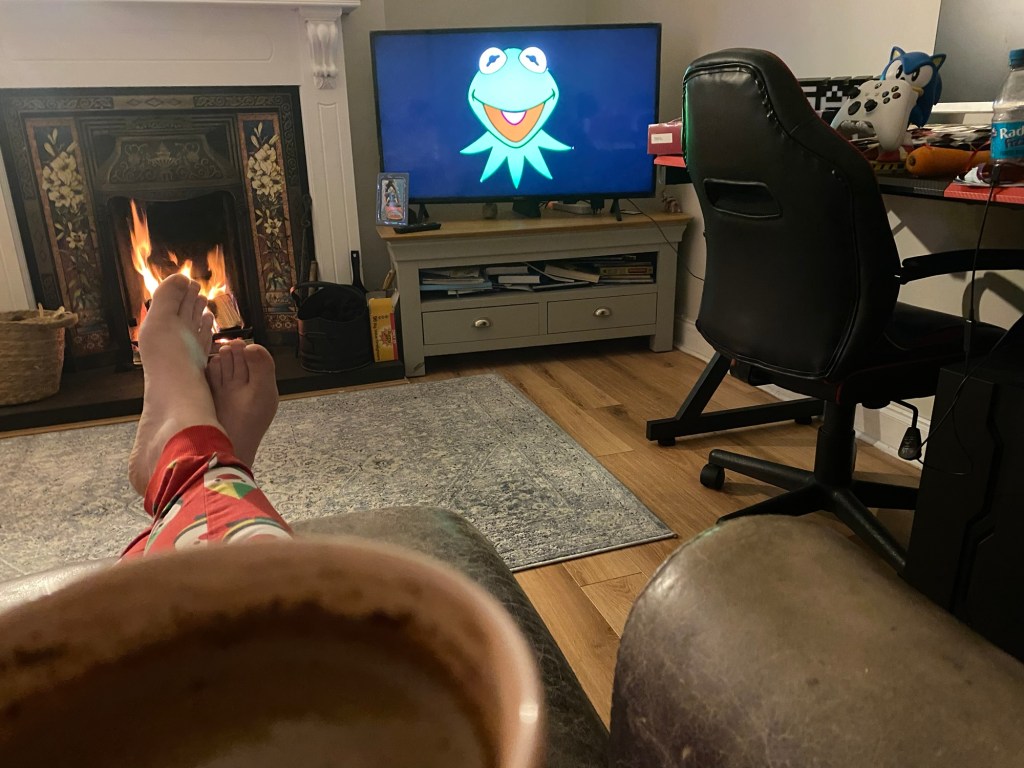

Er, is this thing on? Ok here goes…..It all started on a grey weekday afternoon. Mummy was at work. I was cuddled up on the sofa with my young son watching He-Man on Netflix.

Er, is this thing on? Ok here goes…..It all started on a grey weekday afternoon. Mummy was at work. I was cuddled up on the sofa with my young son watching He-Man on Netflix.